Introduction and Method:

The Wild Alberta Food Project is an interdisciplinary venture created by the author of this report, Scott McKenzie. While the task of this project is to assess how regenerative agriculture (RA) can improve Alberta’s food system, this report may be viewed as an argument through which this project intends to change people’s minds about agriculture. To this end, an exhaustive account of RA’s benefits will be relayed in conjunction with the public policy initiatives required to facilitate food system transformation in Alberta.[1]

The following question bears answering at the onset of this report to serve as a signpost for the findings revealed in steps six through nine: What is the connection between healthy soil, healthy people, economic prosperity, and regenerative agriculture?

In short, a food system based on RA has healthy, carbon rich soil that uses biological fuel instead of chemical fertilizers to produce healthier more nutrient rich food than can be produced using industrial production methods.[2] Beyond the positive socioeconomic benefits of a healthier population, farmer wellbeing is improved as they witness the positive environmental outcomes that result from RA practices.[3] Instilled with increased self-efficacy and a greater capacity for change, farmers are encouraged to complete the agricultural transition process and help others do the same, creating what researchers refer to as positive feedback loops.[4] Further, there is much anecdotal evidence that farmers who transition to RA practices are able to earn more profit per acre due to fewer input costs and a more resilient landscape better equipped to handle the negative effects of climate change like drought, and increasingly frequent catastrophic weather events.[5] When combined with a growing market for RA products, visible corporate support from large corporations like Nestle, Pepsi, McCain, and Cargill, and increased acceptance from the financial sector, the economics of RA should be viewed as a positive rather than a negative.[6] Through public policy that incentivises ecologically responsible decisions, such as RA adoption, the interconnections between the environment, human health, and socioeconomic conditions can be managed to produce a sustainable positive feedback loop in which the quality of all three is improved.

One of the challenges facing RA is the lack of a universal definition. This can be attributed to RA practices being context specific vis-à-vis soil composition, and economic costs. However, for the purpose of this project RA may be defined as an approach to farming that uses soil conservation as the entry point to regenerate and contribute to multiple provisioning, regulating and supporting services, with the objective that this will enhance not only the environmental, but also the social and economic dimensions of sustainable food production.[7] As Alberta-specific research is aggregated, an Alberta-specific definition will emerge.

Using Repko and Szostak’s stage and process model of disciplinary integration expressed in Interdisciplinary Research: Process and Theory, insights from the disciplines of ecology, sociology, economics, and public policy have been assembled, evaluated and integrated to produce a more comprehensive understanding of how regenerative agriculture can improve Alberta’s food system. This report provides an exhaustive account of this process and consists of ten steps:

-

Define the problem or state the research question.

-

Justify using an interdisciplinary approach.

-

Identify relevant disciplines.

-

Conduct a literature search.

-

Develop adequacy in each relevant discipline.

-

Analyze the problem and evaluate each insight or theory.

-

Identify conflicts between insights or theories and their sources.

-

Create common ground between concepts and theories.

-

Construct a more comprehensive understanding.

-

Reflect on how an interdisciplinary approach has enlarged your understanding of the problem.[8]

Although there are numerous Alberta-based RA ventures (Regenerative Agriculture Lab, The Simpson Centre, to name a few), New Zealand is widely considered to be the global leader in RA research. Consequently, multiple insights reflected in this report are gleaned from New Zealand’s highly collaborative and comprehensive white paper titled Regenerative Agriculture in Aotearoa New Zealand – Research Pathways to Build Science-Based Evidence and National Narratives, henceforth referred to as New Zealand’s White Paper.[9] For reference, a report is considered to be a white paper if it is government sponsored.

While reading this report it will be helpful to consult the appendices as indicated. Particularly Appendix C, which contains a collated and annotated list of identifiers for all theories and subsequent disciplinary conclusions and assumptions used during the integration process. If you have downloaded this as a .docx file, you need only hover the curser over an identifier to view the corresponding annotation in the appendix.

1. The Problem: Alberta's Food System

The impact of population growth and poor environmental stewardship has humanity facing several food system related crises including climate change and global food insecurity. The earth cannot bear the environmental cost of feeding an additional four billion people by the end of the century unless agricultural practices undergo dramatic change. Further exacerbating these issues and exposing food system fragility is the COVID-19 pandemic which undermined food supply chains. Globally, poor diets are the leading cause of disease, accounting for 20% of premature disease related deaths.[10] The nature and severity of the challenges connecting agriculture and food value chains to nutrition, health, and global ecosystems can no longer be overlooked. The argument for food system transformation is now irrefutable.[11]

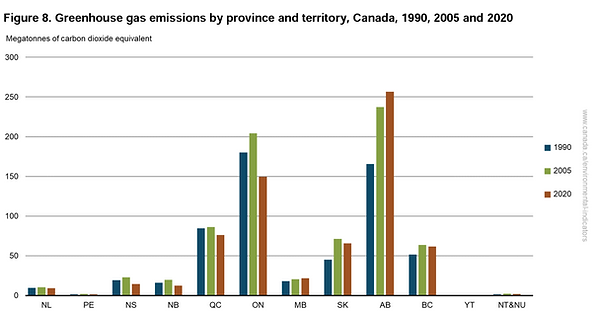

Of all Canadian provinces, Alberta has the most beef cattle, the second largest number of farms and farmed area and is one of Canada’s largest crop producers. Consequently, Alberta is responsible for the highest level of both agricultural and total greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions.[12] Figure 1.1 below illustrates that in 2020 Alberta emitted over 256.5 megatonnes of carbon dioxide, 106.9 megatonnes more than the next largest emitter, Ontario. Moreover, of the top five emitters, Alberta is the only province that saw an increase in emissions between 2005 and 2020. To be fair, according to UCalgary affiliate The Simpson Centre, Alberta’s agricultural sector produced only approximately 10% of these emissions and even reduced its emissions by 7.4% between 2005 and 2019.[13] Nevertheless, the prospect of agricultural carbon sinks lowering this number to 0%, and also significantly offsetting Alberta’s total GHG emissions is tantalizing, and one of the main drivers of RA support.

Figure 1.1 GHG emissions by province.[14] Source: Canada.ca 2020.

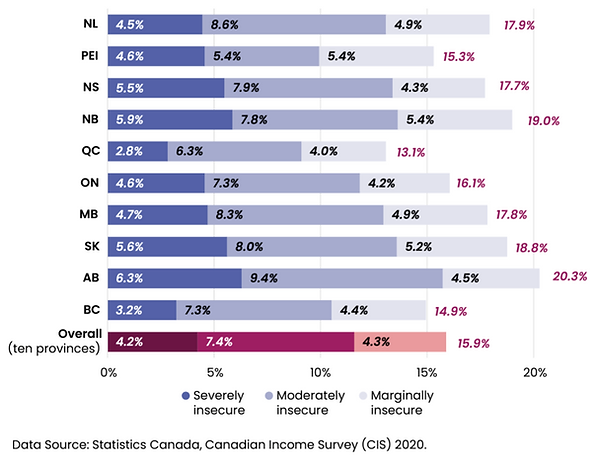

Figure 1.2 below illustrates that in 2021, Alberta had the highest rate of food insecurity in Canada at 20.3%, with a particularly concerning 6.3% of Albertans experiencing severe food

insecurity and another 9.4% experiencing moderate food insecurity.[15]

Figure 1.2 2021 Household food insecurity in Canada by province. Source: Tarasuk, Li, and St. Germain 2022.

Compared to pre-pandemic levels, Alberta saw a 73% increase in food bank usage since 2019, more than double the national rate of increase and the highest rate in the country.[16] Compounding the urgency of the problem is the rate of degradation witnessed since 2011 when Alberta’s rate of food insecurity was just 8.1% and ranked third lowest in Canada behind only Manitoba and Newfoundland.[17]

A 2018 Alberta Health Services report, named poor nutrition as a leading cause of chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. Using fruit and vegetable consumption as an indicator of overall nutrition in Alberta, the study concluded that 2 of 3 Albertans were not eating enough fruits and vegetables at an estimated cost to the province of at least one billion dollars annually.[18] A 2021 multidisciplinary study of nutrition among Alberta children indicated that this trend is not slowing and is being propagated across generations, as Alberta’s youth nutrition was given an overall D grade.[19] The relationship between poor nutrition, chronic disease, and financial cost is further highlighted in a 2021 study which concluded that the treatment of chronic disease consumes 67% of all direct health care costs nationally and adds up to $190 billion annually.[20] Adopting healthy lifestyles such as healthy eating, active living, not smoking, and moderate alcohol consumption can prevent up to 80% of type-2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and 40% of cancers.[21] Among these lifestyle risk factors for chronic diseases, an unhealthy diet has been shown to have the greatest impact.[22] Diabetes Canada predicts a 42% increase in Alberta diagnoses (either type 1 or 2) by 2032 at an additional estimated yearly cost of $692 million to the health care system.[23] To avoid this, and several other costly inevitabilities associated with the trends highlighted here, Alberta must transform the underlying food system contributing to the proliferation of such trends. Fortunately, a viable option exists and is already being implemented around the world, and indeed within Alberta as well: regenerative agriculture.

Achieving transformation will require a major shift in mindsets – particularly regarding more critical evaluations of the status quo, and roles and responsibilities of public sector actors versus businesses in influencing dietary demand. Additionally, because Alberta’s environmental health, human health, and economic prosperity are interconnected outcomes, exerting significant influence on one another, transforming Alberta’s food system will require environmental, social, and economics changes.[24]

The economic burden of an increasingly unhealthy population stemming from poor nutrition combined with high levels of GHG emissions and the highest rates food insecurity in Canada, signal that Alberta’s food system is problematic and must change. In light of these concerns and substantial current literature illustrating the numerous benefits of regenerative agriculture, The Wild Alberta Food Project seeks to answer the following question: How can regenerative agriculture improve Alberta’s food system?

*To view the full report and conclusion, click on the "2023 Report" button at the top of this page.

____________________

Notes

[1]. See Glossary of Terms for definitions of carbon sink, feedback, feedback loop, food insecurity, food system, food value chain, and regenerative farming.

[2]. Courtney White, “Why Regenerative Agriculture?” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 79, no. 3 (2020): 800, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12334.

[3]. 1) Limited disturbance; 2) Armor; 3) Diversity; 4) Living roots; and 5) Integrated Animals. See page 22 for expanded definitions.

[4]. Kimberly Brown, Jackie Schirmer, and Penny Upton, “Can Regenerative Agriculture Support Successful Adaptation to Climate Change and Improved Landscape Health through Building Farmer Self-Efficacy and Wellbeing?", Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 4 (January 2022): 1, accessed December 20, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsust.2022.100170.

[5]. Gabe Brown, Dirt to Soil, (Toronto: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2018), 178.

[6]. Diana Bach, Nova Sayers, and Hannah Weatherford. White Paper: The Business Case for Regenerative Agriculture. NSF (www.nsf.org, April 2020 2020). https://www.nsf.org/knowledge-library/white-paper-the-business-case-for-regenerative-agriculture.

[7]. Loekie Schreefel et al., "Regenerative Agriculture – the Soil Is the Base," Global food security 26 (August 2020): 6, accessed December 10, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100404.

[8]. Allan F. Repko and Rick Szostak, Interdisciplinary Research: Process and Theory, 4th ed. (Los Angeles: Sage, 2021).

[9]. A White Paper may be thought of as a collaboration between all stakeholders across a given area of inquiry, such as food systems.

[10]. Patrick Webb et al., “The Urgency of Food System Transformation Is Now Irrefutable,” Nature Food 1, no. 10 (October 2020): 584, accessed February 2, 2023, doi:10.1038/s43016-020-00161-0.

[11]. Webb et al., “The Urgency,” 584-85.

[12]. Nimanthika Lokuge, and Sven Anders, "Carbon Credit Systems in Agriculture: A Review of Literature," The School of Public Policy Publications 15, no. 1 (April 2022): 1, accessed October 14, 2022, https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/sppp/article/view/74591.

[13]. The Simpson Centre, Alberta Agriculture Carbon Report Card, 2021, https://simpsoncentre-dashboard.ca/carbon/carbon-report-card/#report-card.

[14]. See Appendix B for detailed breakdown of GHG emission statistics. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/greenhouse-gas-emissions.html.

[15]. Valerie Tarasuk, Tim Li, and Andrée-Anne Fafard St-Germain, Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2021. Toronto: University of Toronto PROOF, 2022. https://proof.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Household-Food-Insecurity-in-Canada-2021-PROOF.pdf.

[16]. “2022 Alberta Hunger Count Findings Atypical Compared to National Trends,” Release: Food Insecurity in Alberta Highest in Canada, Food Banks Alberta, October 27, 2022, accessed October 19, 2022, https://foodbanksalberta.ca/release-food-insecurity-in-alberta-highest-in-canada/.

[17]. Statistics Canada, “Percentage of Households with Food Insecurity, by Province/Territory, CCHS 2011-2012,” last modified November 27, 2015, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2013001/article/11889/c-g/desc/desc04-eng.htm.

[18]. Alberta Health Services, Evidence Review: Nutrition-related Chronic Disease Prevention Interventions, Nutritional Services, Population and Public Health. AHS: 2018, 13, https://abpolicycoalitionforprevention.ca/evidence/albertas-nutrition-report-card/#1569263476904-f213cc81-2fbd.

[19]. Kim Raine, Candace Nykiforuk, and Katerina Maximova, Alberta’s 2021 Nutrition Report Card: On Food Environments for Children and Youth, Publication financed by the Government of Alberta through Alberta Innovates, Edmonton: University of Alberta School of Public Health, 2021, https://abpolicycoalitionforprevention.ca/evidence/albertas-nutrition-report-card/ - 1569263476904-f213cc81-2fbd..

[20]. Siyuan Liu, et al., "The Economic Burden of Excessive Sugar Consumption in Canada: Should the Scope of Preventive Action Be Broadened?", Canadian Journal of Public Health 113, no. 3 (June 2022): 332, https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-022-00615-x.

[21]. Jessica R Lieffers, et al., “The Economic Burden of Not Meeting Food Recommendations in Canada: The Cost of Doing Nothing,” PLOS ONE 13 no. 4 (April 2018): 2, accessed October 19, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196333.

[22]. Liu et al., “The Economic Burden,” 332.

[23]. Diabetes Canada, Diabetes in Alberta: Backgrounder, Ottawa: Diabetes Canada, 2022, 1, https://www.diabetes.ca/DiabetesCanadaWebsite/media/Advocacy-and-Policy/Backgrounder/2022_Backgrounder_Alberta_1.pdf.

[24]. Webb et al., “Urgency,” 584.